The English royal charters granted land to the north to the Plymouth Company, land to the south to the London Company and the land between could be settled first by either company

There were several attempts early in the 17th century to colonize New England by France, England and other countries who were in often in contention for lands in the New World. French nobleman Pierre Dugua de Monts (Sieur de Monts) established a settlement on Saint Croix Island, Maine in June 1604 under the authority of the King of France.

The small St. Croix River Island is located on the northern boundary of present-day Maine. After nearly half the settlers perished due to a harsh winter and scurvy, they moved out of New England north to Port-Royal of Nova Scotia in the spring of 1605.

King James I of England recognizing the need for a permanent mother in New England, granted competing royal charters to the Plymouth Company and the London Company. The Plymouth Company ships arrived at the mouth of the Kennebec River (then called the Sagadahoc River) in August 1607 where they established a settlement named Sagadahoc Colony or more well known as Popham Colony to honor financial backer Sir John Popham.

The colonists faced a harsh winter, the loss of supplies following a storehouse fire and mixed relations with the indigenous tribes.

After the death of colony leader Captain George Popham and a decision by a second leader, Raleigh Gilbert, to return to England to take up an inheritance left by the death of an older brother, all of the colonists decided to return to England. It was around August 1607, when they left on two ships, the Mary and John and a new ship built by the colony named Virginia of Sagadahoc. The 30-ton Virginia was the first English-built ship in North America

Conflict over land rights continued through the early 17th century, with the French constructing Fort Petagouet near present day Castine, Maine in 1613. The fort protecting a trading post and a fishing station was considered the first longer term settlement in New England. The fort traded hands multiple times throughout the 17th century between the English, French and Dutch colonists

Above find an engraved version of Adriaen Block's map of 1614 with some additions and subtractions. On this map the north direction is on the right border.

In 1614, the Dutch explorer Adriaen Block sailed along the coast of Long Island Sound, and then up the Connecticut River to site of present day Hartford, Connecticut. By 1623, the new Dutch West India Company regularly traded for furs there and ten years later they fortified it for protection from the Pequot Indians as well as from the expanding English colonies. They fortified the site, which was named "House of Hope" (also identified as "Fort Hoop", "Good Hope" and "Hope"), but encroaching English colonization made them agree to withdraw in the Treaty of Hartford, and by 1654 they were gone

Pilgrims and Puritans (1620s)

The Pilgrims arrived on the what is now known as the Mayflower from England and the Netherlands late in 1620 to establish Plymouth Colony, which was the first successful British colony in New England to last over a year and one of the first several colonies of British Colonial America following Jamestown, Virginia. Only around half of the one hundred plus passengers on the Mayflower survived that first winter, mostly because of diseases contracted on the voyage. The main reason the Pilgrims came was to obtain free land. Many historians are now agreeing with The Yankee Chef that the practice of free religion and to be away from England including the restrictions on religion played a minor role in the mindset of crossing the treacherous Atlantic to begin a new life here in America.

Above find an engraving of Squanto or Tisquantum teaching the Plymouth colonists to plant corn with fish.

A Native American named Squanto taught the colonists how to catch eel and grow corn the following year (1621). His assistance was remarkable, considering that the Pilgrims were living on the site his deceased Patuxet tribe had established as a village before they were wiped out from diseases brought over by earlier traders from Europe.

Although the Plymouth settlement faced great hardships and earned few profits, it enjoyed a positive reputation in England and may have sown the seeds for further immigration. Edward Winslow and William Bradford published an account of their adventures in 1622, called Mourt's Relation This book glossed over some of the difficulties and challenges carving a settlement out of the wilderness, but it may have been partly responsible for erasing the memory of the Popham Colony (aka Sagadahoc Colony) and encouraging further settlement.

Above find the Frontispiece of "Mourt's Relation," published in 1622 in London. It is the earliest known account of the events in Plymouth Plantation in Massachusetts.

Learning from the Pilgrims harsh experiences of winter in the Plymouth Colony, the Puritans first sent smaller groups in mid-1620s from England to establish colonies, buildings and food supplies. In 1623, the Plymouth Council for New England (successor to the Plymouth Company) established a small fishing village at Cape Ann under the supervision of the Dorchester Company. The first group of Puritans moved to a new town at the nearby Naumkeag, after the Dorchester Company dropped support and fresh financial support was found by Rev. John White. Other settlements were started in nearby areas, however the overall Puritan population remained small through the 1620s. A larger group of Puritans arrived in 1630, leaving England because they were unable to change the Church of England, by their name to "purify" the church. The Puritans had very different religious beliefs compared to the Pilgrims who were Separatists from the Church of England and their colonies were governed independent of each other until the Massachusetts Bay Colony was reorganized in 1691 combining both colonies as the Province of Massachusetts Bay. Prior to the formation of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, the Puritan leaders used the government to enforce the strict religious rules that all Puritans were expected to follow.

Early dissenters of the Puritan laws were often banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The Connecticut Colony was started after a Puritan minister, Thomas Hooker, left Massachusetts Bay with around 100 followers in search of greater religious and political freedom. Another Puritan minister, Roger Williams (theologian) left Massachusetts Bay founding the Rhode Island Colony, while John Wheelwright left with his followers to a colony in present day New Hampshire and shortly thereafter on to present day Maine. The Puritan beliefs of not having to directly pay for school also helped shape the public school system today.

Founding (1630s)

It was the dead of winter, January 1636, when Salem minister Roger Williams had been banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony. The Puritan leaders pushed him out because he preached that government and religion should be separate and also believed the Wampanoag and Narragansett tribes had been treated unfairly.

That winter, the tribes would help Williams to survive and establish a new colony in present-day Rhode Island which he named Providence as in the Divine Providence, for their new colony was unique in its day in expressly providing for religious freedom and a separation of church from state. Roger Williams returned to England two times to prevent the attempt of other colonies to take over Providence and to charter or incorporate Providence and other nearby communities into the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations.

Later in 1636, Thomas Hooker left Massachusetts with one hundred followers and found a new English settlement just north of the Dutch Fort Hoop that would later become Connecticut Colony. The community was first named Newtown then shortly afterwards renamed to Hartford to honor the English town of Hertford. One of the reasons Hooker left was because only admitted members of the church could vote and participate in the government, which he believed should include any adult male owning property. The Connecticut Colony was not the first settlement (Dutch were first), or even the first English settlement (Windsor would be first in 1633), Thomas Hooker would obtain a royal charter and establish Fundamental Orders, considered to be one of the first constitutions in North America. Other colonies, including New Haven and Saybrook would later be merged into the royal charter for the Connecticut Colony.

Impact on native populations

Warrant Signed by Governor Winslow of Plymouth for the Sale of Indian Captives as Slaves.

Estimating the number of Native Americans living in what is today the United States of America before the arrival of the European explorers and settlers has been the subject of much debate. While it is difficult to determine exactly how many Natives lived in North America before Columbus, estimates range from a low of 2.1 million (Ubelaker 1976) to 7 million people (Russell Thornton) to a high of 18 million (Dobyns 1983). A low estimate of around 1 million was first posited by the anthropologist James Mooney in the 1890s, by calculating population density of each culture area based on its carrying capacity. In 1965, the American anthropologist Henry Dobyns published studies estimating the original population to have been 10 to 12 million. By 1983, he increased his estimates to 18 million. He took into account the mortality rates caused by infectious diseases of European explorers and settlers, against which Native Americans had no immunity. Dobyns combined the known mortality rates of these diseases among native people with reliable population records of the 19th century, to calculate the probable size of the original populations. By 1800, the Native population of the present-day United States had declined to approximately 600,000, and only 250,000 Native Americans remained in the 1890s.

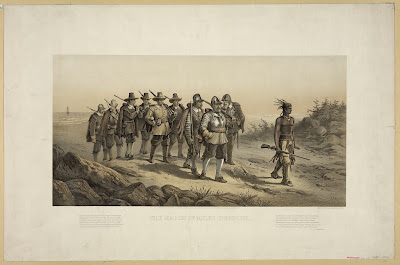

Colored print of nine white men led by an American Indian down a path away from the ocean where a ship is anchored. Two stanzas from Longfellow's, "The Courtship of Miles Standish" appear beneath the image on each side of the title.

Chicken pox and measles, although by this time endemic and rarely fatal among Europeans (long after being introduced from Asia), often proved deadly to Native Americans. Smallpox proved particularly fatal to Native American populations. Epidemics often immediately followed European exploration and sometimes destroyed entire village populations. While precise figures are difficult to determine, some historians estimate that at least 30% (and sometimes 50% to 70%) of some Native populations died after first contact due to Eurasian smallpox. One element of the Columbian exchange suggests explorers from the Christopher Columbus expedition contracted syphilis from indigenous peoples and carried it back to Europe, where it spread widely. Other researchers believe that the disease existed in Europe and Asia before Columbus and his men returned from exposure to indigenous peoples of the Americas, but that they brought back a more virulent form, syphillis.

A 17th century Native American fireplace found in Massahusetts

In 1618–1619, smallpox killed 90% of the Native Americans in the area of the Massachusetts Bay. Historians believe many Mohawk in present-day New York became infected after contact with children of Dutch traders in Albany in 1634. The disease swept through Mohawk villages, reaching the Onondaga at Lake Ontario by 1636, and the lands of the western Iroquois by 1679, as it was carried by Mohawk and other Native Americans who traveled the trading routes.[50] The high rate of fatalities caused breakdowns in Native American societies and disrupted generational exchanges of culture.

Between 1754 and 1763, many Native American tribes were involved in the French and Indian War/Seven Years War. Those involved in the fur trade in the northern areas tended to ally with French forces against British colonial militias. Native Americans fought on both sides of the conflict. The greater number of tribes fought with the French in the hopes of checking British expansion. The British had made fewer allies, but it was joined by some tribes that wanted to prove assimilation and loyalty in support of treaties to preserve their territories. They were often disappointed when such treaties were later overturned. The tribes had their own purposes, using their alliances with the European powers to battle traditional Native enemies.

King Philip's War

King Phillip, Second Chief

King Philip's War sometimes called Metacom's War or Metacom's Rebellion, was an armed conflict between Native American inhabitants of present-day southern New England and English colonists and their Native American allies from 1675–1676. It continued in northern New England (primarily on the Maine frontier) even after King Philip was killed, until a treaty was signed at Casco Bay in April 1678.[citation needed] According to a combined estimate of loss of life in Schultz and Tougias' "King Philip's War, The History and Legacy of America's Forgotten Conflict" (based on sources from the Department of Defense, the Bureau of Census, and the work of Colonial historian Francis Jennings), 800 out of 52,000 English colonists of New England (1 out of every 65) and 3,000 out of 20,000 natives (3 out of every 20) lost their lives due to the war, which makes it proportionately one of the bloodiest and costliest in the history of America.[citation needed] More than half of New England's ninety towns were assaulted by Native American warriors. One in ten soldiers on both sides were wounded or killed.

The Metacomet Trail in Connecticut, near Rattlesnake Mountain south of Route 6 in Farmington.

The war is named after the main leader of the Native American side, Metacomet, Metacom, or Pometacom, known to the English as "King Philip." He was the last Massasoit (Great Leader) of the Pokanoket Tribe/Pokanoket Federation & Wampanoag Nation. Upon their loss to the Colonists and the attempted genocide of the Pokanoket Tribe and Royal Line, many managed to flee to the North to continue their fight against the British (Massachusetts Bay Colony) by joining with the Abanaki Tribes and Wabanaki Federation

Foundations for freedom

Some Europeans considered Native American societies to be representative of a golden age known to them only in folk history. The political theorist Jean Jacques Rousseau wrote that the idea of freedom and democratic ideals was born in the Americas because "it was only in America" that Europeans from 1500 to 1776 knew of societies that were "truly free."

“ Natural freedom is the only object of the policy of the [Native Americans]; with this freedom do nature and climate rule alone amongst them ... [Native Americans] maintain their freedom and find abundant nourishment... [and are] people who live without laws, without police, without religion. ”

The Iroquois nations' political confederacy and democratic government have been credited as influences on the Articles of Confederation and the United States Constitution Historians debate how much the colonists borrowed from existing Native American governmental models. Several founding fathers had contact with Native American leaders and had learned about their styles of government. Prominent figures such as Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin were more involved with leaders of the Iroquois Confederacy, based in New York. John Rutledge of South Carolina in particular is said to have read lengthy tracts of Iroquoian law to the other framers, beginning with the words, "We, the people, to form a union, to establish peace, equity, and order..."

“ As powerful, dense [Mound Builder] populations were reduced to weakened, scattered remnants, political readjustments were necessary. New confederacies were formed. One such was to become a pattern called up by Benjamin Franklin when the thirteen colonies struggled to confederate: 'If the Iroquois can do it so can we,' he said in substance. ”

In October 1988, the U.S. Congress passed Concurrent Resolution 331 to recognize the influence of the Iroquois Constitution upon the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights. Those who argue against Iroquoian influence point to lack of evidence in U.S. constitutional debate records, and democratic U.S. institutions having ample antecedents in European ideas.

During the American Revolution, the newly proclaimed United States competed with the British for the allegiance of Native American nations east of the Mississippi River. Most Native Americans who joined the struggle sided with the British, hoping to use the American Revolutionary War to halt further colonial expansion onto Native American land. Many native communities were divided over which side to support in the war. The first native community to sign a treaty with the new United States Government was the Lenape.

Lenape performing traditional dance, dressed as the Mesingoholikan, an incarnation of the spirit who negotiated between people and the spirits of animals they killed

For the Iroquois Confederacy, the American Revolution resulted in civil war. The only Iroquois tribes to ally with the colonials were the Oneida and Tuscarora.

Frontier warfare during the American Revolution was particularly brutal, and numerous atrocities were committed by settlers and native tribes alike. Noncombatants suffered greatly during the war. Military expeditions on each side destroyed villages and food supplies to reduce the ability of people to fight, as in frequent raids in the Mohawk Valley and western New York. The largest of these expeditions was the Sullivan Expedition of 1779, in which American colonial troops destroyed more than 40 Iroquois villages to neutralize Iroquois raids in upstate New York. The expedition failed to have the desired effect: Native American activity became even more determined.

American Indians have played a central role in shaping the history of the nation, and they are deeply woven into the social fabric of much of American life.... During the last three decades of the twentieth century, scholars of ethnohistory, of the "new Indian history," and of Native American studies forcefully demonstrated that to understand American history and the American experience, one must include American Indians.

The United States was eager to expand, to develop farming and settlements in new areas, and to satisfy land hunger of settlers from New England and new immigrants. The national government initially sought to purchase Native American land by treaties. The states and settlers were frequently at odds with this policy.

George Washington advocated the advancement of Native American society and he "harbored some measure of goodwill towards the Indians."

European nations sent Native Americans (sometimes against their will) to the Old World as objects of curiosity. They often entertained royalty and were sometimes prey to commercial purposes. Christianization of Native Americans was a charted purpose for some European colonies.

“ Whereas it hath at this time become peculiarly necessary to warn the citizens of the United States against a violation of the treaties.... I do by these presents require, all officers of the United States, as well civil as military, and all other citizens and inhabitants thereof, to govern themselves according to the treaties and act aforesaid, as they will answer the contrary at their peril. ”

Back side of an Indian Peace Medal given by President George Washington in 1792, which shows a version of the Great Seal of the United States. The Smithsonian curators believe this medal was awarded on March 13, 1792, at a conference in Philadelphia between an Indian delegation (the Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, Tuscarora, and Stockbridge tribes), and President Washington, the secretary of war, the governor of Pennsylvania, and others

United States policy toward Native Americans had continued to evolve after the American Revolution. George Washington and Henry Knox believed that Native Americans were equals but that their society was inferior. Washington formulated a policy to encourage the "civilizing" process. Washington had a six-point plan for civilization which included,

1. impartial justice toward Native Americans

2. regulated buying of Native American lands

3. promotion of commerce

4. promotion of experiments to civilize or improve Native American society

5. presidential authority to give presents

6. punishing those who violated Native American rights.

Robert Remini, a historian, wrote that "once the Indians adopted the practice of private property, built homes, farmed, educated their children, and embraced Christianity, these Native Americans would win acceptance from white Americans." The United States appointed agents, like Benjamin Hawkins, to live among the Native Americans and to teach them how to live like whites.

“ How different would be the sensation of a philosophic mind to reflect that instead of exterminating a part of the human race by our modes of population that we had persevered through all difficulties and at last had imparted our Knowledge of cultivating and the arts, to the Aboriginals of the Country by which the source of future life and happiness had been preserved and extended. But it has been conceived to be impracticable to civilize the Indians of North America — This opinion is probably more convenient than just. ”

In the late 18th century, reformers starting with Washington and Knox, supported educating native children and adults, in efforts to "civilize" or otherwise assimilate Native Americans to the larger society (as opposed to relegating them to reservations). The Civilization Fund Act of 1819 promoted this civilization policy by providing funding to societies (mostly religious) who worked on Native American improvement.

“ I rejoice, brothers, to hear you propose to become cultivators of the earth for the maintenance of your families. Be assured you will support them better and with less labor, by raising stock and bread, and by spinning and weaving clothes, than by hunting. A little land cultivated, and a little labor, will procure more provisions than the most successful hunt; and a woman will clothe more by spinning and weaving, than a man by hunting. Compared with you, we are but as of yesterday in this land. Yet see how much more we have multiplied by industry, and the exercise of that reason which you possess in common with us. Follow then our example, brethren, and we will aid you with great pleasure.... ”

The British made peace with the Americans in the Treaty of Paris (1783), through which they ceded vast Native American territories to the United States without informing the Native Americans, leading immediately to the Northwest Indian War. The United States initially treated the Native Americans who had fought with the British as a conquered people who had lost their lands. Although many of the Iroquois tribes went to Canada with the Loyalists, others tried to stay in New York and western territories and tried to maintain their lands. Nonetheless, the state of New York made a separate treaty with Iroquois and put up for sale 5,000,000 acres of land that had previously been their territory. The state established a reservation near Syracuse for the Onondagas who had been allies of the colonists.

“ The Indians presented a reverse image of European civilization which helped America establish a national identity that was neither savage nor civilized. ”

First Contact between European Explorers and Iroqoises

Commerce

The earliest colonies in the New England Colonies were usually fishing villages or farming communities along the more fertile land along the rivers. While the rocky soil in the New England Colonies was not as fertile as the Middle or Southern Colonies, the land provided rich resources including timber that was valued for building of homes and ships. Timber was also a resource that could be exported back to England, where there was a shortage of timber. In addition, the hunting of wild life provided furs to be traded and food for the table. The New England Colonies were located near the ocean where there was an abundance of whales, fish and other marketable sea life. Excellent harbors and some inland waterways offered protection for ships and were also valuable for fresh water fishing. The Puritans of the Massachusetts Bay Colony named the settlement on the Shawmut Peninsula as Boston. For most of the early years, Boston was the largest city in all of the British Colonial America. By the end of the seventeenth century, New England colonists had tapped into a sprawling Atlantic trade network that connected them to the English homeland as well as the West African slave coast, the Caribbean's plantation islands, and the Iberian Peninsula. Colonists relied upon British and European imports for glass, linens, hardware, machinery, and other items found around a colonist's household. In contrast to the Southern Colonies, which could produce tobacco, rice, and indigo in exchange for imports, New England's colonies could not offer much to England beyond fish, and furs, respectively. Inflation was a major issue in the economy.

Engraving of a scold's bridle and New England street scene

On 1606-04-10, King James I of England issued two charters, one each for the Virginia Companies, of London and Plymouth, respectively. The purpose of both was to claim land for England and trade. Under the charters, the territory allocated was defined as follows:

Virginia Company of London: All land, including islands within 100 miles from the coast and implying a westward limit of 100 miles , between 34 Degrees (Cape Fear, North Carolina) and 41 Degrees (Long Island Sound, New York) north latitude.

The seal of the London Company, also known as the Charter of the Virginia Company of London

Virginia Company of Plymouth: All land, including islands within 100 miles from the coast and implying a westward limit of 100 miles , between 38 Degrees (Chesapeake Bay, Virginia) and 45 Degrees (Border between Canada and Maine) north latitude. Its charter included land extending as far as present-day northern Maine.

These were privately funded proprietary ventures, and the purpose of each was to claim land for England, trade, and return a profit. The Virginia Company of London successfully established the Jamestown Colony in Virginia in 1607. The region was named "New England" by Captain John Smith, who explored its shores in 1614, in his account of two voyages there, published as A Description of New England.

Plymouth (1620–1643)

The name "New England" was officially sanctioned on November 3, 1620, when the charter of the Virginia Company of Plymouth was replaced by a royal charter for the Plymouth Council for New England, a joint stock company established to colonize and govern the region. In December 1620, a permanent settlement known as the Plymouth Colony was established at present-day Plymouth, Massachusetts by the Pilgrims, English religious separatists arriving via Holland. They arrived aboard a ship named the Mayflower and held a feast of gratitude which became part of the American tradition of Thanksgiving. Plymouth, with a small population and limited size, was absorbed by Massachusetts in 1691.,

In 1638, a "violent" earthquake was felt throughout New England, centered in the St. Lawrence Velley. This was the first recorded seismic event noted in New England

Puritans

The Massachusetts Bay Colony, which would come to dominate the area, was established in 1628 with its major city of Boston established in 1630. The Puritans, a much larger group than the Pilgrims, established the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1629 with 400 settlers. They sought to reform the Church of England by creating a new, pure church in the New World. By 1640, 20,000 had arrived; many died soon after arrival, but the others found a healthy climate and an ample food supply. See Migration to New England (1620–1640).

The Puritans created a deeply religious, socially tight-knit, and politically innovative culture that still influences the modern United States They hoped this new land would serve as a "redeemer nation". They fled England and in America attempted to create a "nation of saints" or a "City upon a Hill": an intensely religious, thoroughly righteous community designed to be an example for all of Europe. Roger Williams, who preached religious toleration, separation of Church and State, and a complete break with the Church of England, was banished and founded Rhode Island Colony, which became a haven for other refugees from the Puritan community, such as Anne Hutchinson

Economically, Puritan New England fulfilled the expectations of its founders. Unlike the cash crop-oriented plantations of the Chesapeake region, the Puritan economy was based on the efforts of self-supporting farmsteads who traded only for goods they could not produce themselves There was a generally higher economic standing and standard of living in New England than in the Chesapeake. Along with agriculture, fishing, and logging, New England became an important mercantile and shipbuilding center, serving as the hub for trading between the southern colonies and Europe

Banished from Massachusetts for his theological heresies, Roger Williams led a group south, and founded Providence, Rhode Island in 1636. It merged with other settlements to form Rhode Island, which became a center for Baptists and Quakers.

On March 3, 1636, the Connecticut Colony was granted a charter and established its own government. The nearby New Haven Colony was absorbed by Connecticut.

Vermont was then unsettled, and the territories of New Hampshire and Maine were then governed by Massachusetts.

The Dominion of New England (1686–1689)

King James II. Oil on canvas. Artist unknown

In 1686, King James II, concerned about the increasingly independent ways of the colonies, in particular their self governing Charters, open flouting of the Navigation Acts and their increasing military power decreed the Dominion of New England, an administrative union comprising all the New England colonies. Two years later, the provinces of New York (New Amsterdam) and the New Jersey, which had been confiscated by force from the Dutch, were added. The union, imposed from the outside, and removing nearly all their popularly elected leaders, was highly unpopular among the colonists. In 1687, when the Connecticut Colony refused to follow a decision of the dominion governor Edmund Andros to turn over their charter, he sent an armed contingent to seize the colony's charter. According to popular legend, the colonists hid the charter inside the Charter Oak tree. Andros' efforts to loot the colonies, replace their leaders and to unify the colonial defenses under his control met little success and the dominion ceased after only three years. After the very popular removal of King James II in the Glorious Revolution of 1689, Andros was arrested and sent back to England by the colonists during the 1689 Boston revolt

1689 - 1775

After the Glorious Revolution in 1689 the charters of most of the colonies were significantly modified with the appointment of Royal Governors to nearly each colony. An uneasy tension existed between the Royal Governors, their officers and the elected governing bodies in the colonies. The governors wanted essentially unlimited arbitrary powers and the different layers of locally elected officials resisted as best they could. In most cases the local town governments continued operating as self-governing bodies as they had before the Royal Governors showed up and to the extent possible ignored the Royal Governors. This tension eventually led to the American Revolution when the states formed their own governments. The colonies were not formally united again until 1776 as newly formed states, when they declared themselves independent states in a larger (but not yet federalist) union called the United States.

By 1723, Puritan cultural and religious influence had declined substantially in Boston. One of Ben Franklin's first printed works decried frivolity among Harvard students.

Focused on shipping as well as production, New England conducted a robust trade within the English domain in the mid-18th century. They exported to the Caribbean: pickled beef and pork, onions and potatoes from the Connecticut valley, codfish to feed their slaves, northern pine and oak staves from which the planters constructed containers to ship their sugar and molasses, Narragansett Pacers from Rhode Island, and "plugs" to run sugar mills.

The New England States were initially colonized by about 30,000 settlers between 1620 and 1640, a period now referred to as "The Great Migration." There was little additional immigration until the Irish influx of the 1840s and '50s in the wake of the potato famine. The almost one million inhabitants 130 years later at the time of the Revolution were nearly all descended from the original settlers, whose 3 percent annual natural growth rate caused a doubling of population every 25 years. Their beliefs and ancestry were nearly all shared and made them into what was probably the largest more-or-less homogeneous group of settlers in America. Their high birth rate continued for at least a century more, making the descendants of these New Englanders well represented in nearly all states today. In the 18th century and the early 19th century, New England was still considered to be a very distinct region of the country, as it is today. During the War of 1812, there was a limited amount of talk of secession from the Union, as New England merchants, just getting back on their feet, opposed the war with their greatest trading partner — Great Britain.

Aside from the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, or "New Scotland," New England is the only North American region to inherit the name of a kingdom in the British Isles. New England has largely preserved its regional character, especially in its historic sites. Its name is a reminder of the past, as many of the original English-Americans have migrated further west.

After the American Revolutionary War, Connecticut and Massachusetts ceded tracts of land to the federal government that they had claimed in the Northwest Territory and the Western Reserve exceeding their modern day areas.

Population and economy

Benjamin Franklin in 1772, after examining the wretched hovels in Scotland surrounding the opulent mansions of the land owners, said that in New England every man is a property owner, "has a Vote in public Affairs, lives in a tidy, warm House, has plenty of good Food and Fuel, with whole clothes from Head to Foot, the Manufacture perhaps of his own family."

Population

The regional economy grew rapidly in the 17th century, thanks to heavy immigration, high birth rates, low death rates, and an abundance of inexpensive farmland.[12] The population grew from 3000 in 1630 to 14,000 in 1640, 33,000 in 1660, 68,000 in 1680, and 91,000 in 1700. Between 1630 and 1643, about 20,000 Puritans arrived, settling mostly near Boston; after 1643 fewer than fifty immigrants a year arrived. The average size of a completed family 1660-1700 was 7.1 children; the birth rate was 49 babies per year per 1000 people, and the death rate was about 22 deaths per year per thousand people. About 27 percent of the population comprised men between 16 and 60 years old.

Economy

The region's economy grew steadily over the entire colonial era, despite the lack of a staple crop that could be exported. All the provinces, and many towns as well, tried to foster economic growth by subsidizing projects that improved the infrastructure, such as roads, bridges, inns and ferries. They gave bounties and subsidies or monopolies to sawmills, grist mills, iron mills pulling mills (which treated cloth), salt works and glassworks. Most important, colonial legislatures set up a legal system that was conducive to business enterprise by resolving disputes, enforcing contracts, and protecting property rights. Hard work and entrepreneurship characterized the region, as the Puritans and Yankees endorsed the "Protestant Ethic", which enjoined men to work hard as part of their divine calling.

The benefits of growth were widely distributed, with even farm laborers better off at the end of the colonial period. The growing population led to shortages of good farm land on which young families could establish themselves; one result was to delay marriage, and another was to move to new lands further west. In the towns and cities, there was strong entrepreneurship, and a steady increase in the specialization of labor. Wages for men went up steadily before 1775; new occupations were opening for women, including weaving, teaching, and tailoring. The region bordered New France, and in the numerous wars the British poured money in to purchase supplies, build roads and pay colonial soldiers. The coastal ports began to specialize in fishing, international trade and shipbuilding—and after 1780 in whaling. Combined with a growing urban markets for farm products, these factors allowed the economy to flourish despite the lack of technological innovation.

Education

A New England Dame school in old colonial times, 1713. Engraving. (Bettman Archive)

New England has always had a commanding position and the history of American education. The first American schools in the thirteen colonies opened in the 17th century. Boston Latin School was founded in 1635 and is both the first public school and oldest existing school in the United States. Cremin (1970) stresses that colonists tried at first to educate by the traditional English methods of family, church, community, and apprenticeship, with schools later becoming the key agent in "socialization." At first, the rudiments of literacy and arithmetic were taught inside the family, assuming the parents had those skills. Literacy rates seem to have been much higher in New England, and much lower in the South. By the mid-19th century, the role of the schools had expanded to such an extent that many of the educational tasks traditionally handled by parents became the responsibility of the schools.

All the New England colonies required towns to set up schools, and many did so. In 1642 the Massachusetts Bay Colony made "proper" education compulsory; other New England colonies followed. Similar statutes were adopted in other colonies in the 1640s and 1650s. The schools were all male, with few facilities for girls. In the 18th century, "common schools," appeared; students of all ages were under the control of one teacher in one room. Although they were publicly supplied at the local (town) level, they were not free, and instead were supported by tuition or "rate bills."

The larger towns in New England opened grammar schools, the forerunner of the modern high school. The most famous was the Boston Latin School, which is still in operation as a public high school. Hopkins School in New Haven, Connecticut, was another. By the 1780s, most had been replaced by private academies. By the early 19th century New England operated a network of elite private high schools, now called "prep schools," typified by Phillips Andover Academy (1778), Phillips Exeter Academy (1781), and Deerfield Academy (1797). They became coeducational in the 1970s, and remain highly prestigious in the 21st century.

Colleges

Colleges and churches were often copied from European architecture; Boston College was originally dubbed Oxford in America

Memorial Hall at Harvard College

Harvard College was founded by the colonial legislature in 1636, and named after an early benefactor. Most of the funding came from the colony, but the college early began to collect endowment. Harvard at first focused on training young men for the ministry, and one general support from the Puritan colonies. Yale College was founded in 1701, and in 1716 was relocated to New Haven, Connecticut. The conservative Puritan ministers of Connecticut had grown dissatisfied with the more liberal theology of Harvard, and wanted their own school to train orthodox ministers. Dartmouth College, chartered in 1769, grew out of school for Indians, and was moved to its present site in Hanover, New Hampshire, in 1770. Brown University was founded by Baptists in 1764 as the College in the English Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations.

Girls

Tax-supported schooling for girls began as early as 1767 in New England. It was optional and some towns proved reluctant. Northampton, Massachusetts, for example, was a late adopter because it had many rich families who dominated the political and social structures and they did not want to pay taxes to aid poor families. Northampton assessed taxes on all households, rather than only on those with children, and used the funds to support a grammar school to prepare boys for college. Not until after 1800 did Northampton educate girls with public money. In contrast, the town of Sutton, Massachusetts, was diverse in terms of social leadership and religion at an early point in its history. Sutton paid for its schools by means of taxes on households with children only, thereby creating an active constituency in favor of universal education for both boys and girls.

Historians point out that reading and writing were different skills in the colonial era. School taught both, but in places without schools reading was mainly taught to boys and also a few privileged girls. Men handled worldly affairs and needed to read and write. Girls only needed to read (especially religious materials). This educational disparity between reading and writing explains why the colonial women often could read, but could not write and could not sign their names—they used an "X".[25]

1770-1900

.

New England, especially Boston, was the center of revolutionary activity in the decade before 1775, with Massachusetts politicians Samuel Adams, John Adams, and John Hancock as leaders. New Englanders, like all Americans, were very proud of their political freedoms and local democracy, which they felt was increasingly threatened by the British imperial government. The main grievance was taxation, which colonists argued could only be imposed by their own legislatures, and not by the Parliament in London. Their political cry was, "No taxation without representation! On December 16, 1773, when a ship was planning to land taxed tea in Boston, local activists calling themselves the Sons of Liberty, disguised themselves as Indians, raided the ship, and dumped all the tea into the harbor. This Boston Tea Party outraged British of officials, and the King and Parliament decided to punish Massachusetts.

Parliament passed the Intolerable Acts in 1774 that brought stiff punishment.

”The able Doctor, or America Swallowing the Bitter Draught.” Etching. From the London Magazine, May 1, 1774. British Cartoon Collection. Prints and Photographs Division. LC-USZC4-5289. Prime Minister Lord North, author of the Boston Port Bill, forces the ”Intolerable Acts,” or tea, down the throat of America, a vulnerable Indian woman whose arms are restrained by Lord Chief Justice Mansfield, while Lord Sandwich, a notorious womanizer, pins down her feet and peers up her skirt. Behind them, Mother Britannia weeps helplessly. This British cartoon was quickly copied and distributed by Paul Revere

It closed the port of Boston, the economic lifeblood of the Commonwealth, and ended self-government, putting the people under military rule. The patriots set up a shadow government, which the British Army attack on April 18, 1775 at Concord. On the 19th, in the Battles of Lexington and Concord, where the famous "shot heard 'round the world" was fired, British troops, were forced back into the city by the local militias, under the control of the shadow government. The British army controlled only the city of Boston, and it was quickly brought under siege. The Continental Congress to control the war, sending General George Washington to take charge. he forced the British to evacuate in March 1776. After that, the main warfare moves south, but the British made repeated raids along the coast, and seized part of Rhode Island and Maine for a while. On the whole, the patriots controlled 99 percent of the New England population.

Early national period

After independence, New England ceased to be a meaningful political unit, but remained a defined historical and cultural region consisting of its now-sovereign constituent states. By 1784, all of the states in the region had introduced the gradual abolition of slavery, with Vermont and Massachusetts introducing total abolition in 1777 and 1783, respectively. During the War of 1812, there was a limited amount of talk of secession from the Union, as New England merchants, just getting back on their feet, opposed the war with their greatest trading partner—Britain.[28] Delegates from all over New England met in Hartford in the winter of 1814-15. The gathering was called the Hartford Convention. The twenty-seven delegates met to discuss changes to the US Constitution that would protect the region from similar legislation and attempt to keep political power in the region.

In 1820, as part of the Missouri Compromise, the territory of Maine, formerly a part of Massachusetts, was admitted to the Union as a state. Today, New England is always defined as coextensive with the six states of Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont.

For the remainder of the antebellum period, New England remained distinct. In terms of politics, it often went against the grain of the rest of the country. Massachusetts and Connecticut were among the last refuges of the Federalist Party, and, when the Second Party System began in the 1830s, New England became the strongest bastion of the new Whig Party. The Whigs were usually dominant throughout New England, except in the more Democratic Maine and New Hampshire. Leading statesmen — including Daniel Webster — hailed from the region. New England was distinct in other ways. It was, as a whole, the most urbanized part of the country (the 1860 Census showed that 32 of the 100 largest cities in the country were in New England), as well as the most educated. Notable literary and intellectual figures produced by the United States in the Antebellum period were New Englanders, including Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, John Greenleaf Whittier, George Bancroft, William H. Prescott, and others

New England was an early center of the industrial revolution. In Beverly, Massachusetts the first cotton mill in America was founded in 1787, the Beverly Cotton Manufactory. The Manufactory was also considered the largest cotton mill of its time. Technological developments and achievements from the Manufactory led to the development of other, more advanced cotton mills later, including Slater Mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. Several textile mills were already underway during the time. Towns like Lawrence, Massachusetts, Lowell, Massachusetts, Woonsocket, Rhode Island, and Lewiston, Maine became famed as centers of the textile industry following models from Slater Mill and the Beverly Cotton Manufactory. The textile manufacturing in New England was growing rapidly, which caused a shortage of workers. Recruiters were hired by mill agents to bring young women and children from the countryside to work in the factories. Between 1830 and 1860, thousands of farm girls came from their rural homes in New England to work in the mills. Farmers’ daughters left their homes to aid their families financially, save for marriage, and widen their horizons. They also left their homes due to population pressures to look for opportunities in expanding New England cities. Stagecoach and railroad services made it easier for the rapid flow of workers to travel from the country to the city. The majority of female workers came from rural farming towns in northern New England. As the textile industry grew, immigration grew as well. As the number of Irish workers in the mills increased, the number of young women working in the mills decreased. At first the mills employed young Yankee farm women; they then used Irish and French immigrants.

New England and areas settled from New England, like Upstate New York, Ohio's Western Reserve and the upper midwestern states of Michigan and Wisconsin, proved to be the center of the strongest abolitionist sentiment in the country. Abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison and Wendell Phillips were New Englanders, and the region was home to anti-slavery politicians like John Quincy Adams, Charles Sumner, and John P. Hale. When the anti-slavery Republican Party was formed in the 1850s, all of New England, including areas that had previously been strongholds for both the Whig and the Democratic Parties, became strongly Republican, as it would remain until the early 20th century, when immigration turned the formerly solidly Republican states of Lower New England towards the Democrats.

New England was the first region to experience large scale colonization in the early 17th century, beginning in 1620, and it was dominated by East Anglian Calvinists, better known as the Puritans. The religious fundamentalism of the Puritans created a cuisine that was austere, disdainful of feasting and with few embellishments. Eating was seen as a largely practical matter and one of the few occasions when New Englanders would engage in massive bouts of eating and drinking was at funerals, times when even children might drink large amounts of alcohol. Age was one of the most important signs of authority and determined eating practices; though Puritan society was less stratified, particularly compared to the southern colonies, heads of the household and their spouses would often eat separately from both children and servants. Though New England had a great abundance of wildlife and seafood, traditional East Anglian fare was preferred, even if it had to be made with New World ingredients. Baked beans and pease porridge were everyday fare, particularly during the winter, and usually eaten with coarse, dark bread. At first it was made with a mixture of wheat and maize (corn), but after a disease called wheat rust struck in the 1660s, it was made of rye and maize, creating what has later been known as "rye 'n' injun". Vegetables with meat boiled thoroughly was a popular dish, and unlike many other regions in North American colonies, they were cooked together, rather than separately, and frequently without seasoning. Baking was a particular favorite of the New Englanders and was the origin of dishes today seen as quintessentially American, such as apple pie and the baked Thanksgiving turkey.

New England is a northeastern region of the United States, including the six states of Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. The American Indians cuisine became part of the cookery style that the early colonists brought with them. The style of New England cookery originated from its colonial roots, that is to say practical, frugal and willing to eat anything other than what they were used to from their British roots. Much of the cuisine started with one-pot cookery, which resulted in such dishes as succotash, chowder, baked beans, and many, many others.

The Backcountry

The last major wave of British immigrants to the colonies took place from 1720–1775. About 250,000 people travelled across the Atlantic primarily to seek economic betterment and to escape hardships and famine. Most of these came from the borderlands of northern Britain and were of Scots-Irish or Scottish descent. Many were poor and therefore accustomed to hard times, setting them apart from the other major British immigrant groups. They settled in what would come to be known generally as the "Backcountry", on the frontier and in the highlands in the north and south. The backcountry relied heavily on a diet based on mush made from soured milk or boiled grains. Clabber, a yoghurt-like food made with soured milk, was a standard breakfast dish and was eaten by backcountry settlers of all ages. This dietary habit was not shared by other British immigrant groups and was equally despised by those still in Britain. The Anglican missionary Charles Woodmason, who spent time among Ulster Irish immigrants, described them as depending "wholly on butter, milk, clabber and what in England is given to hogs". Oatmeal mush was a popular meal in the British borderlands and remained popular in America. The only difference was that the oatmeal was replaced by corn, and is still known today in the South as grits. Cakes of unleavened dough baked on bakestones or circular griddles were common and went by names such as "clapbread", "griddle cakes" and "pancakes". While the potato had originated in South America, it did not became established in North America until it was brought to the colonies by northern British settlers in the 18th century and became an important backcountry staple along with corn. Pork had been a food taboo among northern Britons and the primary meat had been sheep. In the American colonies the raising of sheep was not as efficient and mutton was therefore replaced with pork. The habit of eating "sallet" or "greens" remained popular, but the vegetables of the Old World were replaced with plants like squashes, gourds, beans, corn, land cress and pokeweed. The distinctive cooking style of the British borderlands and the American backcountry was boiling. Along with clabber, porridge and mushes, the typical dishes were various stews, soups and pot pies.

Two meals per day, a hearty breakfast and an early supper, was the standard. Food was eaten from wooden or pewter trenchers with two-tined forks(not universal until well into the 18th century), large spoons and hunting knives. Dishware was not popular since it was easily breakable and tended to dull knives quickly. Unlike the Quakers and Puritans, feasting with an abundance of food and drink was never discouraged and practiced as often as was feasible.

An apparent lack of fastidiousness in preparing the food provoked further criticism from many sources. The Anglican Woodmason characterized backcountry cooking as "exceedingly filthy and most execrable". Others told of matrons washing their feet in the cookpot, that it was considered unlucky to wash a milk churn and that human hairs in butter were considered a sign of quality. These descriptions seem to be confirmed by an old saying attributed to Appalachian housewives: "The mair [more] dirt the less hurt". Another expression of backcountry hardiness was the lack of appreciation of coffee and tea. Both were described as mere "slops" and were deemed appropriate only for those who were sick or unfit for labor

Diet before the American Revolution

When colonists arrived in America, they planted familiar crops from the Old World with varying degrees of success and raised domestic animals for meat, leather, and wool, as they had done in Britain. The colonists faced difficulties owing to different climate and other environmental factors, but trade with Britain, continental Europe, and the West Indies allowed the American colonists to create a cuisine similar to the various regional British cuisines. Local plants and animals offered tantalizing alternatives to the Old World diet, but the colonists held on to old traditions and tended to use these items in the same fashion as they did their Old World equivalents (or even ignore them if more familiar foods were available). The American colonial diet varied depending on region, with local cuisine patterns established by the mid-18th century.

A number of vegetables were grown in the northern colonies, including turnips, onions, cabbage, carrots, and parsnips, along with pulses and legumes. These vegetables stored well through the colder months. Other vegetables, such as cucumbers, could be salted or pickled for preservation. Agricultural success in the northern colonies came from following the seasons, with consumption of fresh greens only occurring during summer months. In addition to vegetables, a large number of seasonal fruits were grown. Fruits not eaten in season were often preserved as jam, wet sweetmeats, dried, or cooked into pies that could be frozen during the winter months. Some vegetables originating in the New World, including beans, squashes, and corn, were readily adopted and grown by the European colonists. Pumpkins and gourds grew well in the northern colonies and were often used for fodder for animals in addition to human consumption.

Effects of the American Revolution

In 1775, the Continental Congress decreed that no imports would enter the American colonies, nor would any exports move from America to England. Some historians state that this had a profound effect on the agriculture of America, while others state that there was no effect as the domestic market was strong enough to sustain American agriculturists. The dispute lies in the fact that the American economy was highly diverse; there was no standard form of currency, and records were not consistently kept.

Hops, a necessary ingredient to make beer, were not imported during the American Revolution, leading to a decline in beer production.

By the declaration of the American Revolution, with George Washington as its military leader, a number of dietary changes had already occurred in America. Coffee was quickly becoming the normal hot drink of the colonies and a taste for whiskey had been acquired among many of those who could produce it. In fact, in 1774, the first corn was grown in Kentucky specifically for production of American Bourbon whiskey. This step may have established this American spirit in American culture, just as the country was going to war with England. In addition to whiskey coming into favor, a shift began in the consumption of cider over beer. Colonists opted to grow less barley as it was easier to ferment apple cider than to brew beer.[47] Another reason for this change would have been the lack of imported hops needed to brew beer.

As game became scarce and a moratorium was placed on mutton consumption, cattle husbandry increased.

As the American colonies went to war, they needed soldiers, supplies, and lots of them. Soldiers needed uniforms and, as all shipping into the colonies had ceased, wool became an integral commodity to the war effort. During the Revolution the consumption of mutton ceased almost entirely in many areas, and in Virginia it became illegal to consume except in cases of extreme necessity.

. Cattle raising had begun on a small scale during the French-Indian War, but when the American Revolution came, farmers were able to increase their cattle holdings and increase the presence of beef in the American diet. In addition to beef production, the cattle also increased the production of milk and dairy products like butter. This may have contributed to the preference of butter over pork fat, especially in New England

With the arrival of English soldiers by ship, and naval battles on the seas, areas used for salt water fishing became perilous, and lay dormant for much of the war. In addition, many of the fishing vessels were converted into warships. Before the war, there was often talk about the excess of lobsters and cod off the shores of New England. This seemed to change during and after the war, due to the vast numbers of ships and artillery entering the ocean waters. Once lobster harvesting and cod fishing was reestablished, most fishermen found that the lobster and cod had migrated away from the shores.

Where Americans had a historic disdain for the refineries of French cooking, that opinion, at least in a small part, began to change with the American alliance with the French. In the first American publication of Hannah Glasse’s Art of Cookery Made Easy, the insults toward French dishes disappeared. A number of Bostonians even attempted to cook French cuisine for their French allies, sometimes with comedic results when entire frogs were put into soups rather than just their legs. Nonetheless, the alliance supported a friendship with France that later resulted in a large migration of French cooks and chefs to America during the French Revolution.

The American diet was changed through this friendship as well as due to the changes forced through boycott and hostilities with England. After a time, trade did resume with the West Indies but was limited to necessities. Items that sustained the war effort in America were traded, with crops such as rice from the Carolinas shipped out and coffee beans imported in order to brew America’s new beverage of choice.

Seafood

Saltwater fish eaten by the American Indians were cod, bass, sole, flounder, herring, halibut, eel, sturgeon, smelt, and salmon. Whale was hunted by American Indians off the coast and used for their meat and oil. Crustacean included shrimp, lobster, quahog, soft-shell clams and crabs. Much of this shellfish contributes to New England tradition, the clambake. The clambake as known today is a colonial interpretation of an American Indian tradition. Oysters were eaten as were mussels and periwinkles

Early Native Americans utilized a number of cooking methods in early American Cuisine, that have been blended with early European cooking methods to form the basis of American Cuisine. Grilling meats was common. Spit roasting over a pit fire was common as well. Vegetables, especially root vegetables were often cooked directly in the ashes of the fire. As early American Indians lacked the proper pottery that could be used directly over a fire, they developed a technique which has caused many anthropologists to call them "Stone Boilers". They would heat rocks directly in a fire and then add the bricks to a pot filled with water until it came to a boil so that it would cook the meat or vegetables in the boiling water.

When the colonists came to America, their initial attempts at survival included planting crops familiar to them from back home in England. In the same way, they farmed animals for clothing and meat in a similar fashion. Through hardships and eventual establishment of trade with Britain, the West Indies and other regions, the colonists were able to establish themselves in the American colonies with a cuisine similar to their previous British cuisine. There were some exceptions to the diet, such as local vegetation and animals, but the colonists attempted to use these items in the same fashion as they had their equivalents or ignore them if they could. The manner of cooking for the American colonists followed along the line of British cookery up until the Revolution. The British sentiment followed in the cookbooks brought to the New World as well.

There was a general disdain for French cookery, even with the French Huguenots and French-Canadians. One of the cookbooks that proliferated in the colonies was The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, by Hannah Glasse. She wrote of disdain for the French style of cookery, stating “the blind folly of this age that would rather be imposed on by a French booby, than give encouragement to a good English cook!” Of the French recipes, she does add to the text she speaks out flagrantly against the dishes as she “… think it an odd jumble of trash.” Reinforcing the anti-French sentiment was the French and Indian War from 1754-1764. This created a large anxiety against the French, which influenced the English to either deport many of the French, or as in the case of the Acadians, they migrated to Louisiana. The Acadian French did create a large French influence in the diet of those settled in Louisiana, but had little or no influence outside of Louisiana.

Common ingredients

The American colonial diet varied depending on the settled region in which someone lived. Local cuisine patterns had established by the mid 18th century. The New England colonies were extremely similar in their dietary habits to those that many of them had brought from England. A striking difference for the colonists in New England compared to other regions was seasonality. While in the southern colonies, they could farm almost year round, in the northern colonies, the growing seasons were very restricted. In addition, colonists’ close proximity to the ocean gave them a bounty of fresh fish to add to their diet, especially in the northern colonies. Wheat, however, the grain used to bake bread back in England was almost impossible to grow, and imports of wheat were far from cost productive. Substitutes in cases such as this included cornmeal. The Johnnycake was a poor substitute to some for wheaten bread, but acceptance by both the northern and southern colonies seems evident and it became a much loved staple of the Yankee diet.

As many of the New Englanders were originally from England game hunting was often a pastime from back home that paid off when they immigrated to the New World. Much of the northern colonists depended upon the ability either of themselves to hunt, or for others from which they could purchase game. This was the preferred method for protein consumption over animal husbandry, as it required much more work to defend the kept animals against American Indians or the French.

Livestock and game

Commonly hunted and eaten game included deer, bear, lake dwellers and wild turkey. The larger muscles of the animals were roasted and served with currant sauce, while the other smaller portions went into soups, stews, sausages, pies, and pasties. In addition to game, colonists' protein intake was supplemented by mutton. The Spanish in Florida originally introduced sheep to the New World, but this development never quite reached the North, and there they were introduced by the Dutch and English. The keeping of sheep was a result of the English non-practice of animal husbandry. The animals provided wool when young and mutton upon maturity after wool production was no longer desirable. The forage-based diet for sheep that prevailed in the Colonies produced a characteristically strong, gamy flavor and a tougher consistency, which required aging and slow cooking to tenderize.

Fats and oils

A number of fats and oils made from animals served to cook much of the colonial foods. Many homes had a sack made of deerskin filled with bear oil for cooking, while solidified bear fat resembled shortening. Rendered pork fat made the most popular cooking medium, especially from the cooking of bacon. Pork fat was used more often in the southern colonies than the northern colonies as the Spanish introduced pigs earlier to the South. The colonists enjoyed butter in cooking as well, but it was rare prior to the American Revolution, as cattle were not yet plentiful.

Alcoholic drinks

Prior to the Revolution, New Englanders consumed large quantities of rum and beer, as maritime trade provided them relatively easy access to the goods needed to produce these items: Rum was the distilled spirit of choice, as the main ingredient, molasses, was readily available from trade with the West Indies.Due to New England's involvement in the Triangle Trade in the 18th century, molasses and rum were common in New England cuisine. Well into the 19th century, molasses from the Caribbean and honey were staple sweeteners for all but the upper class. Prior to Prohibition, some of the finest rum distilleries were located in New England.

Further into the interior, however, one would often find colonists consuming whiskey, as they did not have similar access to sugar cane. They did have ready access to corn and rye, which they used to produce their whiskey. However, until the Revolution, many considered whiskey to be a coarse alcohol unfit for human consumption, as many believed that it caused the poor to become raucous and unkempt drunkards. Yet one item, hops, important for the production of beer, did not grow well in the colonies. Hops only grew wild in the New World, and as such, importation from England and elsewhere became essential to beer production. In addition to these alcohol-based products produced in America, imports were seen on merchant shelves, including wine and brandy.

Hard apple cider was by far the most common alcoholic beverage available to colonists. This is because apple trees could be grown locally throughout the colonies, unlike grapes and grain which did not grow well at all in New England. Cider was also easier to produce than beer or wine, so it could be made by farmers for their own consumption. Since it was not imported, it was much more affordable to the average colonist than beer or wine. Apple trees were planted in both Virginia and the Massachusetts Bay Colony as early as 1629. Most of these trees were not grafted, and thus produced apples too bitter or sour for eating; they were planted expressly for making cider. Before the Revolution, New Englanders consumed large quantities of rum and beer as maritime trade provided relatively easy access to the goods needed to produce these items. Rum was the distilled spirit of choice as molasses, the main ingredient, was readily available from trade with the West Indies. In the continent's interior, colonists drank whiskey, as they had ready access to corn and rye but did not have good access to sugar cane.

Beer was such an important consumable to Americans that they would closely watch the stocks of barley held by farmers to ensure quality beer production. In John Adams' correspondence with his wife Abigail, he asked about the quality of barley crops to ensure adequate supply for the production of beer for himself and their friends. However, hops, essential to production of beer, did not grow well in the colonies. It only grew wild in the New World, and needed to be imported from England and elsewhere. In addition to these alcohol-based products produced in America, merchants imported wine and brandy. Beer was not only consumed for its flavor and alcohol content, but because it was safer to drink than water, which often harbored disease-causing microorganisms. Even children drank small beer.

Union Oyster House (1826) in Boston is the oldest continuously operating restaurant in America

Even today, traditional cuisine remains a strong part of New England's identity. Some of its plates are now enjoyed by the entire United States, including clam chowder, baked beans, and homemade ice cream. In the past two centuries, New England cooking was strongly influenced and transformed by Irish Americans, the Portuguese fishermen of coastal New England, and Italian Americans.

State dishes and staples

Connecticut is known for its apizza (particularly the white clam pie), shad and shadbakes, grinders (including the state-based Subway chain), and New Haven's claim as the birthplace of the hamburger sandwich at Louis' Lunch in 1900. Italian-inspired cuisine is dominant in the New Haven area, while southeastern Connecticut relies heavily on the fishing industry. Irish American influences are common in the interior portions of the state, including the Hartford area. Hasty pudding is sometimes found in rural communities, particularly around Thanksgiving.

Maine is known for its lobster. Relatively inexpensive lobster rolls (lobster meat mixed with mayonnaise and other ingredients, served in a grilled hot dog roll) are often available in the summer, particularly on the coast. Northern Maine produces potato crops, second only to Idaho in the U.S. Moxie, America's first mass-produced soft drink and the official state soft drink, is known for its strong aftertaste and is found throughout New England. Although originally from New Jersey, wax-wrapped salt water taffy is a popular item sold in tourist areas. Wild blueberries are a common ingredient or garnish, and blueberry pie (when made with wild Maine blueberries) is the official state dessert. Red snappers — natural casing frankfurters colored bright red — are considered the most popular type of hot dog in Maine. The whoopie pie is the official state treat. Finally, the Italian sandwich is popular in Portland and southern Maine—Portland restaurant Amato's claims to have invented the Italian sandwich (specifically, a submarine sandwich made with ham, cheese, tomato, raw peppers, pickles and cheese, served with or without oil, salt and pepper) in 1902. The city of Portland, Maine with its numerous nationally renowned restaurants such as Fore Street, was ranked as Bon Appétit magazine's "America's Foodiest Small Town" in 2009.

Coastal Massachusetts is known for its clams, haddock, and cranberries, and previously cod. Boston is known for, among other things, baked beans, bulkie rolls, and various pastries. Hot roast beef sandwiches served with a sweet barbecue sauce and usually on an onion roll is popular in Boston's surrounding area. The North Shore area is locally known for its roast beef establishments. Apples are grown commercially throughout the Commonwealth Because of the landlocked, hilly terrain common plant foods in Massachusetts are similar to those of interior northern New England- including potatoes, maple syrup and wild blueberries. Dairy production is also prominent in this central and western area. Cuisine in western Massachusetts had similar immigrant influences as the coastal regions, though historically strong Eastern European populations instilled kielbasa and pierogi as common dishes.

Southern New Hampshire cuisine is similar to that of the Boston area, featuring fish, shellfish and local apples. As with Maine and Vermont, French-Canadian dishes are popular, including tourtière, which is traditionally served on Christmas Eve, and poutine. Corn chowder, which is similar to clam chowder but with corn and bacon replacing the clams, is also common. Portsmouth is known for its orange cake, often containing cranberries.

Rhode Island and bordering Bristol County, Massachusetts are known for Rhode Island clam chowder (clear chowder), quahog (hard clams), johnnycakes, coffee milk, celery salt, milkshakes known as "cabinets" (called "frappes" elsewhere in New England), grinders, pizza strips, clam cakes, the chow mein sandwich, and Del's Frozen Lemonade. Another food item popular in Rhode Island and southern Massachusetts is called a "hot wiener" or "New York System wiener," although, ironically, they are unknown in New York (including Coney Island). This food consists of a wiener (similar to a hot dog but skinnier and more orange in color) on a steamed roll with meat sauce and, often, mustard and raw onions ("all the way"). Portuguese influences are becoming increasingly popular in the region, with Italian cooking already long established. The coastal communities and islands, including Block Island, offer more colonial New England fare than the more recent immigrant-influenced varieties found around the Providence area.

Vermont produces Cheddar cheese and other dairy products. It is known in and outside of New England for its maple syrup. Maple syrup is used as an ingredient in some Vermont dishes, including baked beans. Rhubarb pie is a common dessert and has been combined with strawberries in late spring.

Typical foods of New England

Various types of seafood (often fried, baked, broiled, or boiled):

Cod, haddock, halibut, scrod, shad, salmon and trout

Lobster, scallops, clams, quahogs, mussels, steamers

Fried clams

Lobster roll, made with a New England-style hotdog bun

Crab cake

New England clam bake, also known as New England Clam Boil

American chop suey

Anadama bread

Apple cider, hot apple cider, and hard cider

Apple cider doughnuts and apple cider cake

Apple pie (traditionally served with sharp cheddar cheese, often for breakfast), apple crisp and apples themselves bought from local orchards.

Blueberries, especially in blueberry pie, blueberry pancakes with maple syrup, and blueberry muffins

Boston baked beans

Boston creme doughnuts and other pastries

Boston creme pie

Brown bread, not to be confused with whole-wheat bread; a molasses-sweetened bread, often studded with raisins, typically steamed in a coffee can

Chowders of various types, such as clam chowder, corn chowder, fish chowder, etc.

Cranberry cocktail, cranberry mash/crushed cranberries, jellied cranberries, cranberry sauce, cranberry relish, and cranberry bread

Fluffernutter

Concord grapes

Frappes, or cabinets in Rhode Island (see milkshakes)

Hasty pudding

Hot buttered rum

Ice creams from local dairies as well as from commercial producers like Ben & Jerry's

Indian pudding

Johnny cakes

New England boiled dinner

New England Pot Roast

Parker House Rolls

Popovers

Red flannel hash

Rhubarb pie, strawberry rhubarb pie, and rhubarb jam

Succotash

Toll House cookies (the original chocolate chip cookies)

Whoopie pies

New England also has its own food language. In New England, hot and cold sandwiches in elongated rolls are called subs or grinders, and in still some sections of Greater Boston as Spukkies. This is opposed to the appellations hoagies or heroes in other sections of the country. Sub is short for submarine sandwich, for which Boston, Massachusetts is one of three main claimants for inventing. In Maine, the Italian sandwich—a variation specifically made up of ham or salami, cheese, peppers, pickles, tomatoes and optional oil—is popular, though usually kept distinct from other subs.

New England hot dog rolls are split on top instead of on the side.

No comments:

Post a Comment